Masterclass

Trailers

Monsieur Ibrahim et les Fleurs du Coran

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

View all trailers

- Home

- Literature

- Novels

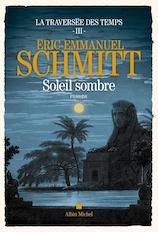

Crossing Time, Volume III – The Sun Goes Down

Summary

Publication date: 2 November 2022

Continuing his journey through the history of humankind, Noam wakes up from a long sleep on the banks of the Nile in 1650 BC and launches into an exhilarating tour of Memphis, the capital of the two kingdoms of Egypt. Times have certainly changed. From brothels to the house of the dead and from Hebrew districts to the Pharoah’s palace, he discovers an extraordinary civilisation handed down on rolls of papyrus; a civilisation that worships the River Nile from which it arose, that mummifies the dead, invents the afterlife and builds temples and pyramids to gain access to eternity. But Noam’s heart is raging, his mind occupied by one idea: to get even with his enemy and at last find contented immortality with his beloved Noura.

In Volume III of Crossing Time, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt takes readers to Ancient Egypt, a civilisation that will flourish for more than three thousand years. Replete with surprises, The Sun Goes Down reconstructs the full vibrancy of this world, whose traces our modern world has preserved but which has nevertheless remained an interlude, sublime and enigmatic in equal measure, in the History of humankind.

Reviews

Le Pèlerin - « A bewitching Volume III! »

Having survived the Flood, traversed the Neolithic and discovered Babel and Mesopotamia, Noam continues his exploration of the civilisations and wakes up in 1650 BC on the banks of the Nile. The immortal hero of Crossing Time (La Traversée des temps) leads readers into Ancient Egypt and Memphis, the capital of the two kingdoms. Noam gasps in wonder at the perfection of the pyramids, falls asleep between the stone paws of the enigmatic sphinx, learns about the mumification of bodies being prepared for the next world and entrusts an abandoned baby to Pharoah’s daughter. Combining his story-telling powers with his encyclopaedic knowledge, Schmitt introduces an array of characters who are both touching and instructive about the evolution of humanity. Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has no equal for his ability to beguile readers while adding to their knowledge. His books are always enthralling and never didactic. What talent!

Catherine Lalanne

Livre Hebdo - « And now, to Memphis! »

ERIC-EMMANUEL SCHMITT is a writer who cares a lot about history whatever the period. Time and again, his books have been testimony to that concern. Now, he is fulfilling a plan that has been “his driving force for 30 years” as his publisher explains, a plan to write a book about nothing less than the adventures of humanity told through key moments in its development, from the end of the Neolithic to the industrial age. In fact, the project involves eight books presented as novels but superbly well researched and produced at a rate of knots: two in 2021, Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) and La porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate) and now in 2022 Soleil Sombre (The Sun Goes Down), which takes us to the time of Ancient Egypt and the pharaohs.

We’re not just in the realm of the historical novel in this series, because the author has telescoped epochs. An interlude between episodes thus brings us back to our own worrying present: in Stockholm, survivalist terrorists decide to wipe out 15-year-old Britta Thorsen, the youthful face of international environmentalism. She is the daughter of Noura, a reincarnation of the Goddess Isis, and Sven, a local environmentalist. The series’ narrator is Noam, himself an avatar of Osiris, the brother and passionate lover of his sister Isis/Noura. Hit by a motorcyclist, Britta has fallen into a deep coma. Her family do everything they can to save her life.

The dark force behind all this is Derek, alias Seth, God of Evil and the brother and assassin of Osiris, who appears in the guise of a dog. Back in the time of the pharaohs, Noam lives in Memphis as the paid gigolo of Neferu, the lover of Mery-Ouser-Re, whom she must succeed after marrying his brother Souser (whom she hates). It is she who finds and raises the baby Moses, a Hebrew son. But there’s no summarising the vagaries of the two heroes, Noam and Noura, inside a pyramid...

The whole thing is a wonderfully tangled web, but it’s also brilliant and thoroughly researched. It’s worth reading the footnotes, too, in small print and sometimes pretty long, explaining a historical point or simply adding to the author’s ha’porth of tar. It turns out that, in a novel, you can do what you like. So, for example, the next volume, Book IV, takes us to Greece four centuries before the birth of Christ, who will turn up in Book V.

Jean-Claude Perrier

Sud-Ouest - « With Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down), Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has produced a dazzling account of Ancient Egypt »

Opus III in the eight-part series La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time) takes place in the middle of the three millennia of Ancient Egypt.

Crossing Time (eight volumes, 5,000 pages) has been bubbling under for decades. It’s an ambitious project involving history and philosophy and aiming, not only to plunge readers into the civilisations before our own, but to show how they helped to shape us and how “everything is extremely linked”, to use the expression of Montesquieu, one of the leading figures of the Enlightenment and close to the heart of the author of Oscar and the Lady in Pink.

After the Flood and the Neolithic revolution of Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) followed by Mesopotamia and the construction of the Tower of Babel in La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate), Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down) moves on to Memphis, the opulent city on the banks of the Nile. Schmitt resurrects ruined towers, rebuilds temples and palaces and breathes life into craftsmen, scribes, slaves and dignitaries. The city teems with life and the two heroes, Noam and Noura, immortal companions at the heart of Crossing Time, blend into this fascinating civilisation which, spanning 3,000 years, is also the longest in history.

Encyclopaedic novel

In this encyclopaedic novel peppered with helpful notes, it’s clear that Schmitt’s descriptive skills come in part from his appetite for knowledge and his own lived experience: when he talks about perfumes, he’s smelt the fragrance; when he describes lotions and potions, he’s explored their ingredients in today’s remedies.

Egyptian civilisation appears here in all its paradoxes and entanglements and in everything that seems so incomprehensible to us: the divination of the line of succession, which had to be pure, hence fathers could marry their daughters; the house, home to both the living and the dead who belonged to the same visible and invisible world; the blurred boundaries between the sexes, which allowed women to accede to the throne…

Having sketched this backdrop, Schmitt brings in Moses, who distanced himself from this hectic world and founded a new mentality that would lead to monotheism.

Isabelle de Montvert-Chaussy

Le Pèlerin - « Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: smuggling History on the banks of the Nile! »

For the publication of Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down), Le Pèlerin accompanied the author to the land of Moses and the pharaohs. Your correspondent reports from Egypt on the trail of the immortal Noam.

“A unique interlude of 3,000 years, a historical and geographical oasis: no civilisation has ever lasted so long!” Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt exclaims, contemplating the majestic pyramid of Cheops, its peak vanishing into the white clouds of the sky. For the publication of Book III of Schmitt’s La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time) – Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes down), the book’s publisher Albin Michel invited journalists and the author to Egypt where the novel is set. Elated and charming, the author stood at the foot of the pyramids of Giza Plateau to explain his fascination with the land of the pharaohs and the book’s title.

“Egypt is an oxymoron: it brings together what would become divided, with Greek philosophy and Jewish thought. In Ancient Egypt, everything is connected: life and death – there’s the continuity of the physical being after death; humans and animals – the gods are half-men, half-beasts; male and female – the Nile is hermaphroditic, as strong as a man but life-giving like a woman!” The author is unstoppable. “The reason we get so excited about Egypt, when so little of its culture has come down to us, is that it has preserved its mystery. It’s anti-Cartesian, it defies categories!”

The novelist can hardly contain his delight at discovering the perfection of the pyramids on the religious Giza Plateau, south of Cairo: “This perfect shape suggests humankind’s unity and power”, or his awe at the infinite delicacy of the sculptures in The Museum of Cairo: gods, pharaohs and scribes in diorite, basalt, ivory, cedarwood and sycamore, but also brightly painted sarcophagi, the treasures of Tutankhamen and... mummies. Many of the items have been taken to the brand-new Grand Egyptian Museum next to the pyramids, scheduled to open in 2023, but two mummies, Yuya and Thuya, Tutankhamen’s grandparents, are still on view. And in such superb condition, their facial characteristics beautifully preserved, you feel as though you’re in their presence.

Basing his research on the latest discoveries, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has written at length about the ruses of the priests of Anubis and the rites and practices during mummification. “When archaeologists scanned the mummies, they discovered that the quality of embalmment varied considerably and that sometimes services that had been promised had not been kept. That gave me scope to sketch a vast human comedy!” laughs the author, who depicts the House of Eternity in Memphis with such realism that you feel you’re right beside Noam, watching the shenanigans of the priests of Anubis and the famous jackal-headed Master of Secrets. The author is passionate, too, about the medical remedies and practices already dealt with in his first two volumes, with Tibor, the medicine man. “As a child, I used to go to the faculty of medicine in Lyon where my father was head of the physiotherapy school. There was a room with mummies in it and a collection of medical instruments down the ages. If I hadn’t been a writer, I’d have been a doctor.”

It's impossible not to be impressed by the wealth of so much accumulated information deftly woven into the epic of Noam: this scribe and doctor with an interest in everything, isn’t he Schmitt’s alter ego? The author acknowledges there’s something in it but tempers the suggestion with: “That’s me at my best! Noam doesn’t judge, he adapts, he’s a humanist.” So, what is Schmitt’s secret? How did he bring it all together? “I start by creating a serious library on the subject with opposing opinions, and I zoom in on all the tiny details. My plan, the characters and the events are all stored in my memory. Then, I spend eight or nine months writing and getting what I’ve written checked by Egyptologists.”

In terms of the place, time and characters of this third volume, “I wanted to show ordinary people and especially women, to highlight the major role they played in that period. Egyptologists agree that they were less powerful than Christiane Desroche Noblecourt would have us believe, excellent though her work was, but they weren’t just relegated to the kitchen, they weren’t veiled.” Eric- Emmanuel Schmitt thus creates sassy female characters, like Féfi the perfumer or Méret the singer and harpist.

A sceptical Moses

“Memphis was important because it was the first capital of Egypt, and as there are few traces of it left, I was able to invent it,” he explains, surprised to discover in Memphis Museum a magnificent alabaster sphinx: a colossal Ramses II. After a photo shoot in front of the sphinx, Schmitt declares his choices. “I chose to set the action in about 1650 BC at the time of the volcanic eruption of Santorini in line with events that have come down to us: the arrival of the “darkness that can be felt” (Exodus 10:21) and plagues. In my book, Aaron, Moses’ companion, attributes these “plagues of Egypt” to the God of Moses, but my Moses is more circumspect!” Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, a Christian, has no hesitation in allowing himself this freedom, because he thinks that history and humanity’s tendency to create meaning and myths is compatible with faith and Christ’s message. He uses this freedom to tell his historical tale as well as the myth of Isis and Osiris and to associate Noam, his immortal hero, with today’s transhumanists. “Transhumanism is the contemporary incarnation of the denial of physical death, just like the Egyptians!”

Monumental and beguiling, this saga covering millennia has been in the making in Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt’s mind since he was 25. “I’ve honed my abilities over the years by writing plays, stories, novellas and a handful of full-length novels and it’s all resulted in this series which is making me enormously happy! So, now I’m able to wallow in my love of encyclopaedias and novels and even footnotes. It’s like the antechamber to life: each new book fills me with energy...!”

In the land of Pharoah and Moses. The pyramids

Who has never dreamed of looking on these “forty centuries” of history, as Napoleon Bonaparte put it in 1798? For the community of journalists, to be able to follow Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt on Giza Plateau on the occasion of the publication of Book III in his series of historical novels, is an exceptional opportunity. The full glory of the ancient world is revealed to us by Cheops Pyramid. Here, men who believed in immortality built the most remarkable tombs in which their mummies would await the journey to the beyond. “I find it deeply moving, it connects me to our ancestors and to their mysterious concept of life and death,” the novelist confides.

Muriel Fauriat

Le Figaro - « In the land of the Pharaohs with Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt »

Paradoxically, despite his solid silhouette, like that of his literary mentor Alexandre Dumas, Eric- Emmanuel Schmitt has a high regard for lightness. “The kind of grace you find in people who look forward to what the day will bring in the morning and look forward to what the night will bring in the evening. People who treat life like a party.” Describing himself as “equable and easy-going”, Schmitt admits that he can sometimes be subdued. For that reason, he needs “whimsical folk” like that around him. Their radiance and energy galvanise his own resources and stop him “shutting down”. People such as his friend Danielle Darrieux, whom he cast in Oscar and The Lady in Pink, a monologue for the stage, in 2003 when she was 85 at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. “Danielle,” he asked her. “What is your definition of happiness?” An existential question if ever there was one! “Opening the shutters in the morning. Closing them at night,” was the delightful actor’s reply (she died in 2017).

Over a two-day escapade to Cairo organised by its publisher Albin Michel to mark the publication of Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down), Volume III in Schmitt’s eight-volume history of humanity (“600 pages each, 5,000 in total”, the author insists, starting in the Neolithic with Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) in February 2021), Schmitt seems to embody this tendency, rare as it is these days, to enjoy every minute.

Squeezed into his seat on the night flight from Paris to Cairo, awkwardly straddling the hump of a camel, biding his time under a blazing sun before Cheops Pyramid in Giza, sinking into the floral cushions of an old felucca or tossed about in a tourist bus as it bowls along the gigantic highways that criss-cross the Egyptian capital, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt never loses his good mood for an instant. Smiling and genial, generous and forthcoming and always a good listener, he goes out into the world with elegance and grace.

He's got good reason to be tired, mind you. The author of Monsieur Ibrahim and the Flowers of the Koran (2001) has just returned from a month in Israel where he was staying with Benedictine monks in Jerusalem at the invitation of the Vatican; on 14 November, he will meet Pope Francis in Rome; in the interim, he will have awarded the Prix Goncourt at Drouant’s restaurant in Paris; he’s the dynamic director of the Théâtre Rive Gauche (Paris); he’ll be clocking up round trips to Brussels, his adopted city these last 20 years; plus, he’s already hard at work on Book IV of La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time), this one set in Greece. Nevertheless, here he is for two days in the land of the Pharaohs.

Launching in

For, Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down) takes place in Memphis on the banks of the Nile in 1650 BC, a tipping point when Moses took a group of men out of Egypt “to live and think differently”. Like the previous two books in the saga, Noam, its immortal hero, leads us by way of his memoires through epochs, centuries and civilisations. “I’ve always been exercised by the question: how did we become what we are?” explains Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt in justification of his titanic literary enterprise to popularise history, which he’s been nurturing since the age of 25. “I was a young philosophy graduate from the Ecole Normale Supérieure and I’d just started teaching for the first time, and I wondered how we’d gone from being hunter-gatherers to this,” he says, with a sweeping gesture towards the endless sun-filled scene at our feet: the baking city of Cairo where the shadows are lengthening. “You know, this totally urbanised, populated world: the Anthropocene! What were the stages that got us here?”

And it was then that he had an idea for a character “who would travel through time and tell us his story, and in so doing, tell us our own”. Having found the plotline, he never left off developing the personality of his principal character. “I could see he was going to be a healer, a doctor; I grasped his relationship with the world and his endless curiosity; I could sense his troubles in love, and I knew he had sensitivity and integrity. Noam began to exist.” In fact, he is like Schmitt. Emotions, passions, moments of doubt. So, it seems odd that he waited so long before he began to write, when he could see the plan so precisely at the age of 25. Why did he start out as a playwright with La Nuit de Valognes (Don Juan on Trial, 1991), winning immediate success and opening the way to whatever he wanted to write? Why did he launch into a Protean career, producing plays, novels, short stories, non-fiction and novellas and racking up 53 titles before he ever got going on the series? “I wasn’t ready. When the idea came to me, I knew that I couldn’t yet bring it to fruition. I set myself a target: ‘One day, you’re going to know enough to outline the historical periods, you’ll have enough energy to write that kind of novel.’ It became a life’s project, an intellectual and artistic agenda. It guided my reading for 30 years and every book I wrote was used as a springboard to reach this future one. I tried to extend my repertoire.” But nothing came. “I hated myself for not managing it. Several times I tried, but it was artificial.” What happened? The answer is instantaneous: “My mother died.” Eric- Emmanuel Schmitt’s eyes cloud. I apologise and offer to change the subject. “No, no,” the writer insists. “I can talk about it now, and it’s why I talk about it. For years, there was a little boy in me thinking that his mother was immortal. Then, suddenly, she was gone, like that, at the age of 87. It was a good age to have reached, but it shook me to my core. I realised the clock was ticking and I thought: ‘You’ve had this grand plan in you and you’re not getting down to it!’ Basically, I began writing out of grief. I thought: ‘This is the most important book of my life and my mother will never read it.’ But it was part of the grieving process.” A rebirth? “Yes, she was dead and I had to create life.”

Inspired by the narrative techniques and drama of Alexandre Dumas – “anticipation, surprise, every sentence driving you compulsively on to the next” --, this historical and scientific novel explores the relationship between people and death. Memphis, the capital of the two Egyptian kingdoms and the setting of The Sun Goes Down, was the site of highly sophisticated funerary rites, a feature that allowed the writer to push back boundaries and dare to draw parallels with Silicon Valley-type transhumanism, “this obsession to big-up humankind the way mummies did for the Ancient Egyptians.” But tonight, “in the gentle air,” when night is falling on the remains of a vanished society, he is filled with nostalgia: nostalgia for an oxymoronic outlook that “connects instead of dividing”, nostalgia for Greek reason and monotheistic logic. An approach to the world that makes no distinction between the dead and the living, between animals and humans, and between women and men. In this “poetic blurring of boundaries”, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt feels happy and at peace.

Isabelle Spaak

Le Parisien - « A radiant setting sun! »

In the desert at the foot of the Giza pyramids, in Cairo’s bustling streets, or in the aisles of the Egyptian capital’s spectacular museum, dressed always in his immaculate blue suit, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt is like a fish in the Nile. In his polished shoes and perfectly pressed jacket and shirt he never loses his smile, not even when he’s mobbed by mosquitoes in the searing heat. For, this is the land where the philosopher-novelist set Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down), Book III in the massive eight- part series of his history of humanity, La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time).

Noam, the saga’s immortal hero, lived through the Neolithic in Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) then encountered the builders of Mesopotamia in La porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate). Now in Book III, we catch up with him in Egypt, still outwardly 25 although actually 8,000 years’ old. As instructive and thrilling as its two predecessors, this literary journey lands us in Memphis on the banks of the Nile in 1650 BC, the heyday of the empire of the pharaohs.

“It informed my childhood”

As a child, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt used to like going to his father’s office in the Lyon faculty of medicine where Schmitt père was head of the physiotherapy school. “My childhood was informed by Ancient Egypt. There was a collection of mummies that used to fascinate me and also a fabulous collection of medical instruments down the ages. The amazing thing is that I only very recently made the connection with my hero Noam, who’s a healer through time and a scribe in this third volume.”

Schmitt believes that the reason France has never lost its fascination with Egypt, even after Napoleon and Champollion, is that the ancient civilisation is “anti-Cartesian” and mysterious. “We need something to balance our obsession with rationality. Three-thousand-year-old Mesopotamia was a self-sufficient world in the middle of the desert. Then you’ve got the invention of the afterlife and eternity. When you visit the pyramids, you’re brought into the presence of death in life.”

Lesser-known Memphis: an obvious choice

He could have set the novel in Luxor, Karnak or Abu Simbel, whose magnificence means they need no introduction. Instead, he chose lesser-known Memphis. “It was an obvious choice,” says the author, during a trip to the archaeological site, standing between a majestic sphinx and a vast prone statue of Ramses II.

“Memphis was the first capital of the kingdom of Egypt and the oldest in the world. It was the seat of Egypt’s power and the place where all trade converged. Today, nothing remains of Memphis, which gave me free rein to describe it as I like. A novel is a powerful way of bringing vanished worlds back to life. A novel is the opposite of a ruin.”

The result is a book over 550 pages long, a real page-turner of a novel which, like the first two in the series, is bursting with information and anecdotes. Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt admits Volume III wasn’t the easiest to write in light of all the clichés peddled by the abundance of fact and fiction dealing with Ancient Egypt. He loves Mona Ozouf’s “instructive” sentence, which he took on board to write his humanist epic: “The historical novel is domesticated history.”

In Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down), Schmitt homes in on the lives of ordinary folk, although the sumptuous land of the pharaohs is never far away. We discover a society in which women held important positions, owned property and took young lovers. Isis, the great life-giving goddess, is omnipresent. “The role of women has declined throughout history. Women have lost their positions.

In images of sexual relations, women are on top of men,” explains the Ecole Normale Supérieure philosophy graduate, a self-proclaimed universalist feminist like his mother and Simone de Beauvoir.

Meticulous work

Schmitt’s favourite Egyptologist is Christiane Desroches Noblecourt (1913-2011), who helped save the monuments of Abu Simbel from the threat of a proposed dam. “She was an ardent defender of women... maybe too ardent, because some of her contemporaries thought she went too far. I had to play down the first version of the novel, which gave an even bigger role to the women,” he smiles, adding that, before handing the manuscript over to his editor, he gave it to two Egyptologists to check.

To stick as closely as possible to historical reality, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt ratcheted up his work, which became astonishingly meticulous. “When I start out, I don’t always know what I’m looking for,” he laughs. “I draw up my bibliography, and I like reading contrasting accounts that don’t agree, to find the chinks and crevasses and to design my strategies... And to unearth bizarre anecdotes, like the one about Egyptian women urinating into a bag of barley seeds to see whether they were pregnant. If the seeds germinated, they were!”

Similarly, thanks to the most up-to-date research involving CT scans of mummies, he learned that some embalmers were crooks who didn’t provide the services they offered. “For a novelist, that’s fantastic. I incorporated those scams into my plot. It’s all part of the human comedy!”

The series is set to continue next year, with Noam discovering Athens. “That should be easier,” Schmitt admits, “because Greece was the culture of my apprenticeship. I’m still obsessed by it.”

Sandrine Bajos

Le Point - « Schmitt in the time of the pharaohs »

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt continues his monumental history of humanity. In Volume III, he lands readers in the cradle of Egyptian civilisation. We meet him in Memphis.

“Who’d have thought it? This is extraordinary! You think you know everything about the place where you set your novel, and then you find yourself in it!” Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt is standing in front of the colossal, monolithic sphinx of Memphis, a few kilometres to the south of Cairo and the capital of Ancient Egypt under the Hyksos pharaohs (1650 BC), where the author chose to set Volume III of his monumental project, La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time). “Of course, I knew the Saqqara necropolis a few kilometres from here, but this magnificent sphinx and this limestone colossus of a recumbent Ramses II behind it... no, I’m not familiar with them.” It’s quite something, revealing things to someone already so knowledgeable on the subject. “It’s like Yuval Noah Harai crossed with Alexandre Dumas,” as Albin Michel announced, when Book I of Schmitt’s epic history of humanity came out. Indeed, that’s exactly what it’s like: the scholarship of Harari combined with the fictional flair of Dumas. Schmitt is pursuing his insatiable, dual need to know and to tell stories.

Hedonism. Following on from the Neolithic and the riparian populations of Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) then the builders of Mesopotamia in La Porte due ciel (Heaven’s Gate), Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down) opens with the immortal Noam waking up after a long sleep on the banks of the Nile before setting off to explore Memphis, the capital of the two kingdoms of Egypt. Who holds the wealth and power in this place, who pulls the strings? To deal with the enemy and find Noura, his sister spirit, he must get to the heart of Egypt, “where imagination combines with science, make- belief with rigour and where an extraordinary civilisation is in the making”. From brothels to the House of the Dead, from Hebrew districts to the pharaoh’s palace, by turn a scribe, a lover, an embalmer and a healer, Noam infiltrates Egyptian society and in the process, his author (or is it his double?) fleshes out vanished ages and brings them to life. Schmitt discovered Egypt as a child, not in books but with his father who was head of the physiotherapy school at the faculty of medicine in Lyon. “I often used to ask him to take me with him. They had a collection of mummies that fascinated me. And I came under the spell of their impressive display of medical instruments down the ages. That fascination stayed with me. Noam is passionate about plants, and in all the eras he lives through, he finds out how people are treated and healed. That gives me scope to research the literature of medicinal plants, and there’s nothing that pleases me more!”

Marvelling at the clear night sky over the ruins of Memphis, Schmitt stops in front of the monumental statue of Ramses II, a 10 m-long, prone limestone sculpture discovered intact in 1820 near the entrance to the Temple of Ptah by the Italian Giovanni Battista Caviglia. “I’m trying not to make a noise because it always seems wrong to disturb the dead, doesn’t it? It’s the same with mummies. I almost feel I shouldn’t stare, because the Egyptians never asked to have tourists filing through a museum all day. But hey, I’m only human and my curiosity got the better of me!” He gives a mischievous laugh, betraying his unquenchable hedonism. Like his character Noam, Schmitt is hungry for knowledge and the good things in life. Another Candide, perhaps? No, he knows full well that not everything is for the best. The contemporary Noam we meet in the book, in the passages that fast-forward to our own time, sounds the alarm beside Bretta, a Greta Thunberg lookalike: “Humankind’s occupation of Earth is turning out to be a disaster. Its industries spread pollution, its lifestyle is exhausting fossil energy sources, its carbon footprint is warming the atmosphere [...] and yet, nothing changes: as soon as the details have been observed, they’re put away to the back of everyone’s mind: a data resource that won’t disturb daily life, as if there’s a missing link between knowledge and behaviour.” But Schmitt is an eternal optimist. He has faith in technology the way

the priests of Memphis had faith in Osiris. Egypt invented eternity, Silicon Valley will invent transhumanism.

Dreams. Darkness has fallen on the ancient capital and suddenly, we’re talking about the meaning of the title, Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down). “Egypt is an oxymoron. Egyptian thought predated the distinctions and categories of Greek philosophy and Judeo-Christian thought. There was no boundary between humans and animals, gods and the mineral world, the natural and supernatural world, presence and absence, or between meaning and what was indecipherable. The Egyptians wanted to understand the incomprehensible, and their way of deciphering mystery consisted in telling stories”. Story-telling: something that’s always been an obsession for Schmitt. The little boy who used to visit the faculty of medicine in Lyon has grown up, but he has remained true to those early leanings. For, what is Crossing Time but a child’s dream, a child’s game that consists in imagining a bygone era and inventing a universe? But, like all games, you have to know when to stop. “Leaving Egypt” is the title of book’s closing chapter. Schmitt is already thinking of the next place, Greece, where readers will catch up with Noam before being whisked off to the Holy Land, where the Vatican has suggested Schmitt spend some time to produce a travel journal and personal diary of his odyssey. In a few days, he has an audience with the Pope – another child’s dream coming to fruition.

VICTORIA GAIRIN

Paris Match - « Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt considers the pyramid of ages... »

Paris Match – “Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt considers the pyramid of ages...”

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt tends to treat the past with a degree of nonchalance. L’Evangile selon Pilate (The Bible According to Pilate) was a spectacular retelling of the New Testament. In La Part de l’autre (The Alternative Hypothesis), he turned Hitler into a brilliant student at the Vienna Academy of Fine Art. Like Alexandre Dumas, Schmitt insinuates his way into readers’ minds like a snake in the grass. This time, Noam and Noura, his heroes, who became immortal after they were hit by a thunderbolt, reappear in the court of Mery-Oser-Rê. We follow them into bed with his daughter Nephron, down the streets of Memphis his capital, and we enter the House of Eternity where mortal remains were dealt with. Cue for a trip to Cairo to ask the genial and iconoclastic scholar a few questions.

Paris Match. Is your interest in history a longstanding vocation?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt. My earliest interest was more oriented towards philosophy. I went through the Ecole Normale Supérieure where my tutor was Derrida, and I did my thesis on Diderot and metaphysics. But history is a great support for philosophical thought. I’ve always wanted to write about humanity’s key moments. So now, I’m giving free rein to my obsession with encyclopaedias. I like non-hierarchical knowledge. Knowing how to press grapes is as important as knowing Aristotle. I learned a lot from Diderot!

The surprise in the book are the forward-looking passages with a Greta-Thunberg look-alike.

The character who’s inspired by her falls victim to an attack that leaves her in a coma. She gets taken to California to one of those transhumanist clinics that dream of making us immortal. Total insanity, and similar to the obsession in Egypt, the land of mummification, which saw death as the gateway to another life.

Aren’t you afraid of the reaction from official historians?

I’ve been thinking about this series since I was 25. And, yes, I felt intimidated by what historians would think. But I was reassured by the reactions from Mesopotamia specialists when Book II in the series came out. And I took care to choose a pharaoh who’s been very little documented, Mery- Oser-Rê. It gave me greater freedom. Also, he lived at the time of the volcanic eruption on Santorini, whose disastrous ecological consequences possibly explained the tragic period of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, which are central to the plot.

You treat the Bible with cheerful irreverence. Not everyone will recognise the Moses they’ve learned about...

The history of the Israelites fleeing Egypt isn’t about a slave population escaping from hell. It’s about the exodus of thousands of poor people, Jews and gentiles, evading slavery. In any case, Moses isn’t a Jewish name, it’s Egyptian. Thoutmôsis means “son of Moses”. The founder of the chosen people has been kind of “de-Egyptianised” to magnify the legend.

Ancient Egypt is a fascinating civilisation. It was so far in advance of the rest of the world, but it was wiped off the map by the Persians and the Greeks and Romans. Why was that?

Yes, it’s odd for a civilisation to last 3,000 years – longer than Christianity – then vanish. But it died out because it didn’t adapt or evolve. For the Egyptians, nothing was linear. They didn’t innovate to progress. There’s not actually a word in Egyptian for “invention”. They thought time was circular. Everything worked in cycles: agriculture, faith, politics... Egypt was going backwards towards its past. A pharaoh was perfect when he reproduced successes that had gone before him. The present was only validated by the past.

Did this book require a lot of work?

I work like a navvy! Once I get down to it, I spend eight or nine months working an eight-hour day from morning till suppertime. I start out just with a plan clear in my mind. Then, I go to American university websites or the French National Library to do the research. When I think how I used to do research at the beginning of my career: the National Library, its splendour, the slowness of it all! It makes you want to worship at the altar of the internet! When I need to relax, I pick up my favourite authors, Colette Maupassant, Diderot, and so on.

You’re also a member of the Goncourt Jury – an exacting task if the members who resign are anything to go by!

I could subscribe to everything Virginie Despentes said in the letter she sent when she left! The summer is spent reading next season’s novels. Then there’s the Biography Goncourt, the First Novel Goncourt, the Poetry Goncourt... not to mention the fact that I’m responsible for the Short Story Goncourt. It does get a bit much sometimes.

And that’s not including the Théâtre Rive Gauche on Rue de la Gaîté in Paris, which you own and manage.

I bought it on impulse, when the Parisian theatres were all turning away my adaptation of “The Diary of Anne Frank”... not that that stopped stop them showering me with compliments! They weren’t even tempted when Francis Huster said he wanted to play Otto Frank. I’ve since discovered that it was the most elegant way of bankrupting myself! But what a joy it is!

Albin Michel has said that the series is set to continue. Where does it go after Egypt?

Greece, of course! Fourth century BC. Plato will have a part and the theatre will come centre stage. It was the glorious hour of its invention and I’m going to depict it as it appeared at the time: closer to the craziness of Ariane Mnouchkine than the gravity of Laurent Terzieff.

On the last page of the book, the two heroes are trapped in a royal tomb. Surely the sequel will be somewhat compromised?

Fortunately, there have always been tomb raiders...

Gilles Martin-Chauffier

La Croix - « Chronicler of human history »

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt gazes up, transfixed, at the Giza pyramids. In his elegant blue suit, he seems in a world of his own, deep in thought and in profound contemplation of a vanished civilisation that is nevertheless indelibly inscribed in human history: this is the Egyptian era, which he has reconstituted in his latest book.

Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down) is the third volume in the massive enterprise he began in 2021 with Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost), about the Neolithic, followed by La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate), involving Babel and Mesopotamia. Eight novels and 5,000 pages to tell the history of humankind, from the time of the hunter-gatherers to contemporary revolutions: such is the challenge Schmitt has set himself with his saga about humanity. “I’ve been wanting to do this for decades!” he says.

The epic’s hero, Noam, is immortal, a time-traveller who documents the epochs he traverses. In the Egyptian episode, published to coincide with the celebrations marking two hundred years since the hieroglyphs were deciphered and one hundred years since the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt had to choose a moment in a civilisation that lasted 3,000 years. He settled for 1600 BC, between the pyramids of the Golden Age and the Valley of the Kings, because nothing remains in our own time of Memphis, the capital city.

“The novel is the opposite of a ruin. It brings vanished civilisations back to life.” To that end, he needed to create a structure that would support his history. His first task was therefore to undertake the requisite research, which Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt did himself, such is his passion for research, for surfing and for building bridges between eras and ideas. From Ancient Egypt, he took away the idea that everything is connected: life and death; the present and the after-life; humans and animals; male and female. A philosophy graduate from the prestigious Ecole Normale Supérieure, Schmitt is never far from his narrator describing daily life, following embalmers and reinventing the potions used to cure bodies and souls. “If I hadn’t been a writer, I’d have been a doctor,” declares this indefatigable worker.

The son of two sportspeople – his mother, Jeannine Trolliet was the French 120m champion in 1945, while his father was a French boxing medallist –, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt is a long-distance writer. “I can’t believe what a voracious reader he is!” comments Gilles Haeri, CBO of the publishing house Albin Michel. “That’s what has enabled him to produce such a Protean output,” Philosophical novels, diaries, novellas, plays… Schmitt also appears on stage in person, for example, in Mr Ibrahim and the Flowers of the Koran, either on tour or in his 450-seat theatre on the Left Bank in Paris, an establishment he has owned for the past dozen years. “A childhood dream,” confides the artist, who seems to make a success of whatever he does.

…Sometimes to the point of irritating the critics, but that’s the price he pays for successive bestsellers since his 1991 play La Nuit de Valognes (Don Juan on Trial) and the roof-raising Le Visiteur (The Visitor) in 1993. L’Evangile selon Pilate (The Bible According to Pilate – 2000) was his first experiment in novel-writing, while the series Le Cycle de l’Invisible (The Cycle of Invisible Things), including Oscar et la Dame Rose (Oscar and The Lady in Pink – 2002) and Le Sumo qui ne voulait pas grossir (The Sumo Wrestler Who Would Not Grow Fat – 2009) tackled the major religious traditions in the form of eight philosophical fables. It’s an impressive profile. Today, the former Cherbourg high-school teacher is one of the most widely read and performed contemporary French-language authors in the world.

With his boxer’s nose, white hair and soothing voice, this is a man who never loses his affable exterior. “Eric-Emmanuel is someone fundamentally cheerful. He is impeccably courteous with everyone and exceptionally professional,” Gilles Haeri continues. As a member of the Goncourt Academy with scores of books to read and judge each year, you wouldn’t think this scribe of history had much spare time. A kind of “Minister of Literature” with not a minute free in his diary, he still found time recently to schedule in a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. At the request of Lorenzo Fazzini, head of the Vatican’s publishing house, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt is busy writing up a travel journal of his trip to Jerusalem. On Monday, he had the chance to show his impressions to Pope Francis when the Pope received him at the Vatican.

For this new project, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt not only undertook a pilgrimage but also spent a week at the French School of Biblical and Archaeological Research in Jerusalem, like Régus Debray 20 years ago. “Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt shared our daily life with us,” says Brother Jean-Jacques Pérennès, the School’s director. “He’s an extraordinarily sensitive artist who absorbs contexts, people and places, and he radiates warmth.” In the secular building at Damas Gate, the author told the Dominican monks about his revelation in the desert. When he was 28, he lost his way one night in the vast wastes of the Ahaggar and in that moment he felt that God was near. The experience became a source of endless inspiration: “In trouble, I was approaching a presence. The further I go, the less I doubt. The further I go, the less I question, and the further I go, the more obvious it becomes. Everything has meaning.”

His inspiration. The encyclopaedic quest

“What brings me most happiness in this project is the fact that I can at last indulge my fascination with encyclopaedias! In this saga (La Traversée des temps – Crossing time), I tell the history of history. The encyclopaedic quest is about non-hierarchical knowledge: it’s just as important to know how bread was made in Ancient Egypt as it is to know Aristotle’s metaphysics. Mona Ouzouf said that “the historical novel is history that has been tamed.” I’d always been afraid of starting this project. I thought that the day I began, I’d be condemned to finish, but actually, each new volume refreshes me: I start with the same appetite and the same joy.”

Christophe Henning

Le Figaro Magazine - « A medicinal plant for the reader. Well done! »

And then there were three! After the Neolithic pile dwellers (Paradis perdus – Paradise Lost) and the builders of the Tower of Babel in Babylonian Mesopotamia (La Porte du ciel – Heaven’s Gate), Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt moves to the banks of the Nile for the setting of Volume III in his series about humanity. In Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down), Noam, an immortal being, sets out to discover Memphis, once the capital of the two kingdoms of Egypt. He is looking for Noura, his girlfriend and herself immortal, whom he lost track of on the streets of Babylon in the previous episode. As in the two earlier novels, he must get to grips with the new civilisation he wakes up in and understand the Egyptian mind, for which imagination and knowledge, fantasy and rigour had equal importance.

Brothels in the House of the Dead, Jewish quarters in the pharaoh’s palace: by turns a scribe, a lover an embalmer and a healer, Noam infiltrates Egyptian society and brings suspense to a vanished era. Schmitt is unique in his ability (and his daring) to invent a new epic form that mingles soap opera with philosophy. In this humanistic and erudite fresco, refinement, knowledge and exoticism combine with the optimism of conquest and pervasive, destructive anxiety, to create an intoxicating musical fugue. This history of humanity will act like a medicinal plant on readers who’ve grown tired of auto-fiction and downbeat novels. Schmitt makes us believe in the immortality of his heroes. Well done”.

CHARLES JAIGU

Le Berry - « Superb! »

Soleil sombre (The Sun Goes Down) by Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt. We were all waiting for Part III in La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time), Schmitt’s madcap plan to tell the History of Humanity in eight volumes. Ancient Egypt, where The Sun Goes Down is set, is the chance for this superb scholar and novelist to give full rein to his talents as a terrific and immensely sensitive writer.

Noam, Noura and Derek, the immortal characters from Volumes I and II, are again the book’s heroes. At once a splendid guide to Ancient Egypt and an enchanting fresco, this novel homes in on the theme of love, which is presented in all its myriad forms. The other underlying subjects are death and the birth of religions. Schmitt also addresses urgent issues in our own time. Superb!

Dimanche (Belgique) - « Sphinx more than pyramid! »

Born in the Mesolithic Age, Noam opens his eyes for a third 8me. Now, he’s in Memphis on the banks of the Nile, which he will discover and come to understand before sharing with us this stage of human history.

Curled up beside the Alabaster Sphinx (a symbol of strength, intelligence and gentleness) Noam recharges his baEeries, intrigued by a liEle girl and a cat, Tii. He learns about hieroglyphs, advances in medicine and burial rites, and, above all, he gets to know contemporary Egyp8ans.

Gentle Meret teaches him the meaning of infinite love as opposed to sensual love and pure pleasure. Meret helps him in his work as a healer and takes him to the needy Israelites. Together, they take Pharaoh’s daughter a baby: Moses.

Moses and Aron offer two visions of a single God: while Moses finds humility before His infinite love, Aron includes Him in his discourse.

Reunions with Derek are unexpected and touching. Noura con8nues to be the woman Noam is seeking and will con8nue to seek.

With Tibor, now Imotep, Noam learns about the existence of the soul. The rites and funerary prac8ces of Ancient Egypt are like an echo of 21st-century events, when Eternity Labs tries to save Noura’s daughter with methods sugges8ve of transhumanism.

The pyramid, like Egyp8an society, underpins a structure that benefits everyone in it, built to magnify the grandeur of one man through the toil of men and women who don’t exist, a monument which, like the 3,000 years of Egyp8an civilisa8on, has remained all but unchanged.

Expect an excursion to Egypt that stands out for its insights and scholarship: well worth the trip!

Geneviève IWEINS