Summary

Original play by John Murrell

Adapted by Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt in 2002

It is summer 1922 and Sarah Bernardt’s last under the sun at her home on the island of Belle-Ile-En-Mer. She relives her past with the help of her secretary, Georges Pitou.

Publications

Published by éditions Avant-scène. DVD available from Warner.

Stage Productions

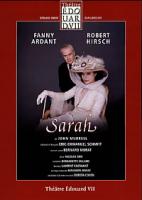

First performed at the Théâtre Edouard VII in Paris in 2002

With Fanny Ardant and Robert Hirsch

Produced by Bernard Murat

Set design by Nicolas Sire

Le Canard Enchaîné - Sara (Ah Sarah, that’ll do!...)

This is a story about pooches, but remarkably talented pooches. Sarah Bernhardt, the glittering actress with a wooden leg (a stage accident, we learn here), daughter of “one of the most dazzling woman in Paris – which is to say, ‘in the world’ – who acquired wealth and a semblance of respectability by having ministers in her bed (well, one at a time as a rule)”, lives out her last summer on Belle-Ile. The year is 1922. The sea twinkles behind the terrace parapet. From time to time, we hear the suck and wash of the waves. Fanny Ardant plays to the full Sarah’s charisma and carnage: enough to convince skeptics of her charm that she was unique.

The calm authority of producer, Bernard Murat, underpins the performance.

At her side is her slave and secretary, Georges Pitou, played by Robert Hirsch with complete disregard for Bernhardt’s obsessions: he swallows them down and comes back for more. On the edge of tragedy, he worries over the bones, goads her on and relishes her crankiness. Seeking inspiration as she writes her Memoirs, the tyrannical superstar – about whom Mark Twain said: “There are five kinds of actresses: bad actresses, fair actresses, good actresses, great actresses – and then there is Sarah Bernhardt” – and Sigmund Freud: “The slightest centimetre of this character is alive and bewitches you…” – obliges her emotional punch-bag to play the clown and impersonate the characters from her past. Such as Judith, the mother who never loved her and thought she was ugly. Sarah dictates the lines, insisting they are realistic and scathing but obstinately rebelling as soon as Pitou offends her, which he does all the time: “I could see you turning rebellious, shock-headed and strident with harsh, Semitic features…” Pitou takes heart by helping himself to a drop of sherry – with Madam’s permission. Pitou protests, puts on airs, refuses to carry a parasol, because at Madam’s great age, especially in her condition, you can’t stay outdoors for long.

The entire show consists of their sado-masochistic, tragicomic duo, bringing together the monumental goddess of the stage with this fragment of delicate porcelain which she proceeds to throttle: “Pitou, you put me in mind of those little creatures one finds on the beach at high tide… They have no nervous system but they writhe and change colour when you touch them. I love you, Pitou.”

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, responsible for this adaptation of John Murrell’s play, must have had a whale of a time writing this tailored script. Though it’s sometimes frustrating not to have representations of the wildest episodes from the life of this fury, whose roles included Phaedra, Lorenzaccio and the Eaglet, who slept in her coffin – not always alone – and whose leg dragging across the wooden floors earned her the nickname “the Bâtonnier”. Manic in New York, wild in Belem beside the Amazon, insolent wherever she went… The sun may always set – it usually does, they note, at the day’s end, when there’s nothing left for Robert Hirsch to do except assume his most moving role as Oscar Wilde on his deathbed in Saint-Tropez meeting the Divine Sarah, herself now near to death: “Promise me you won’t ever die, Sarah.” “I’ll give the idea some thought.”

The curtain falls on a successful show, thanks to Bernard Murat. The curtain may always rise again. It usually does in the morning.